The future is now; “morphing” robots are now a distinct possibility thanks to a metal-foam-alloy which can be made malleable, distorted, and then hardened into a load-bearing block – it even heals if damaged. Unfortunately, the technology still has a ways to go before we get a liquefied terminator or giant mecha combating each other for energon, or the allspark, though. (Not unless heating them to a toasty 144 degrees Fahrenheit is meant to be our secret fail-safe to prevent our inevitable destruction of course.)

The reason for the material’s unusual properties is the combination of a hard yet, under the right circumstances, soft metal and porous rubbery foam.

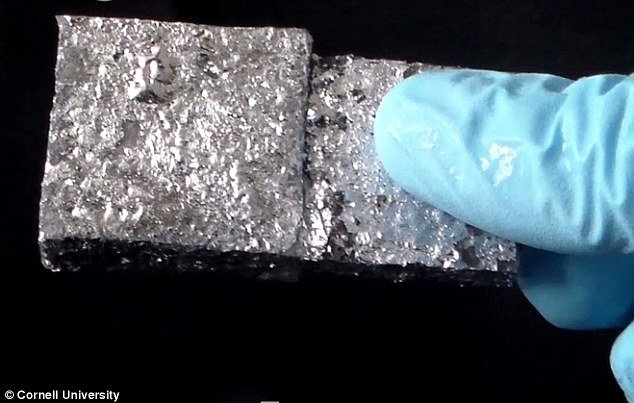

Silicone foam is dipped in liquefied Field’s metal, a soft metal alloy made of bismuth, indium and tin, with a melting point of just 144 degrees Fahrenheit (or 62 degrees Celsius). The material is then placed into a vacuum, which sucks out the air trapped within the pores. The metal seeps into the pores and the entire material allowed to cool into a solid block.

When the material is heated above 144 degrees Farenheit, the alloy melts and allows the entire material to be deformed, but becomes rigid again when cooled. The material can even heal itself if damaged, according to researchers. The material is even biocompatible, and contains no toxic substances.

“Sometimes you want a robot, or any machine, to be stiff,” says Rob Shepherd, Cornell engineering professor who led the research team. “But when you make them stiff, they can’t morph their shape very well. And to give a soft robot both capabilities, to be able to morph their structure but also to be stiff and bear load, that’s what this material does.”

“It’s sort of like us – we have a skeleton, plus soft muscles and skin,” he said. “That’s what this idea is about, to have a skeleton when you need it, melt it away when you don’t, and then reform it.”

The ability to toggle between two shapes, or be molded into a desired form, could at least allow for machines that can be changed to perform better under different circumstances, or even perform completely different functions; for example, a plane, which can change its wing shape mid-flight in order to adjust for different conditions, or dive under water and change into a submersible.

“If you have a wing that’s really broad, you can’t do that because the wing will break off when it hits the water,” said Shepard. “So you need to sweep it back, similar to what a puffin does, and then go under water. And using that new shape, it could be a propeller-driven ship.”

Sources: Cornell, Discovery News, Tech Radar, Journal of Advanced Materials, Daily Mail

This article (Alloy-foam Material Could Provide Basis For Shape-shifting Machines) is a free and open source. You have permission to republish this article under a Creative Commons license with attribution to the author(CoNN) and AnonHQ.com.