They took up arms – some chose lethal weapons, and some chose the mightiest of weapons; the pen – and actively participated in revolutions in different parts of the political world. Here are 10 of those women revolutionaries who stood and fought for what they had believed in…

Lakshmi Sehgal

Captain Lakshmi was a revolutionary of the Indian independence movement, an officer of the Indian National Army, and the Minister of Women’s Affairs in the Azad Hind government. In the 40s, she commanded the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, an all-women regiment that aimed to overthrow the British-chosen Raj in colonial India. In 2002, she stood for Presidential elections, eventually losing the battle to A.P.J. Abdul Kalam.

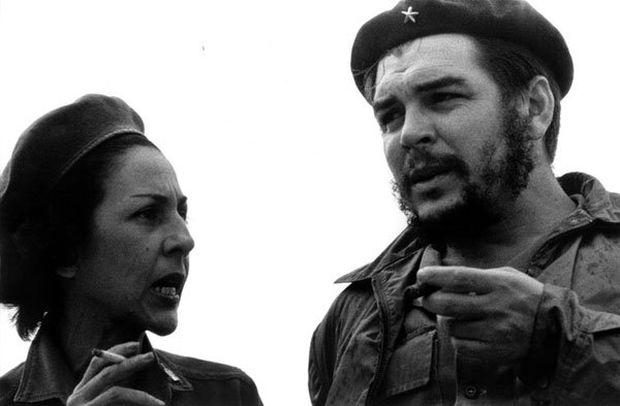

Celia Sanchez

Celia, the woman at the heart of the Cuban Revolution and a close friend of Fidel Castro, together with Frank Pais was one of the first women to assemble a combat squad during the revolution. She made the necessary arrangements throughout the southwest coastal region of Cuba for the Granma landing, and was responsible for organising reinforcements once the revolutionaries landed. In 1957, she joined the guerrillas and served as a messenger.

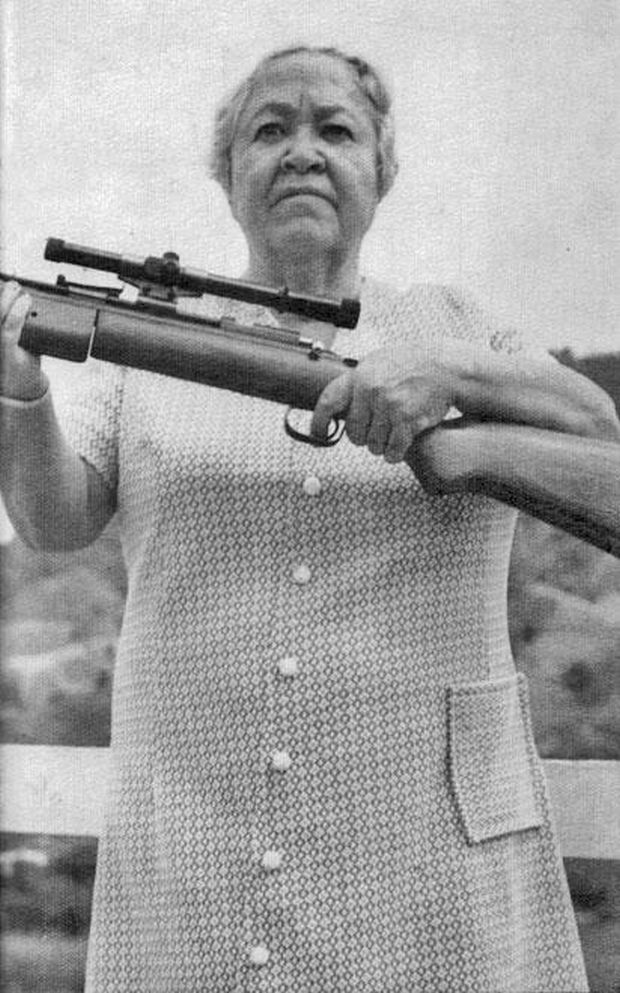

Blanca Canales

Blanca joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party in 1931 and helped organize the Daughters of Freedom, the women’s branch of the Party. As a leader of the Nationalist party in Jayuya, she led an armed revolt in 1950 against the United States, known as the Jayuya Uprising. She took over the police station, burned down the post office, cut the telephone wires, and raised the Puerto Rican flag in defiance of the Gag Law.

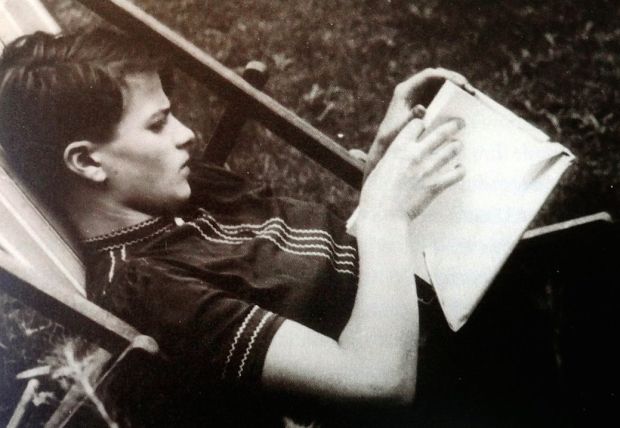

Sophie Scholl

Sophia was a German student and revolutionary active within the White Rose non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany. She is one of the great German heroes who actively opposed the Third Reich during World War II. She was convicted of high treason after having been found distributing anti-war leaflets at the University of Munich with her brother Hans. As a result, they were both executed by guillotine.

Constance Markievicz

Constance was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons (though she did not take her seat). She was also one of the first women in the world to hold a cabinet position (Minister for Labour of the Irish Republic, 1919–1922). She supervised the setting-up of barricades as the Easter Rising of 1916 began and was in the middle of the fighting all around Stephen’s Green, even wounding a British army sniper.

Fashion advice attributed to her was: Dress suitably in short skirts and tough boots, leave your jewels in the bank… and buy a revolver.

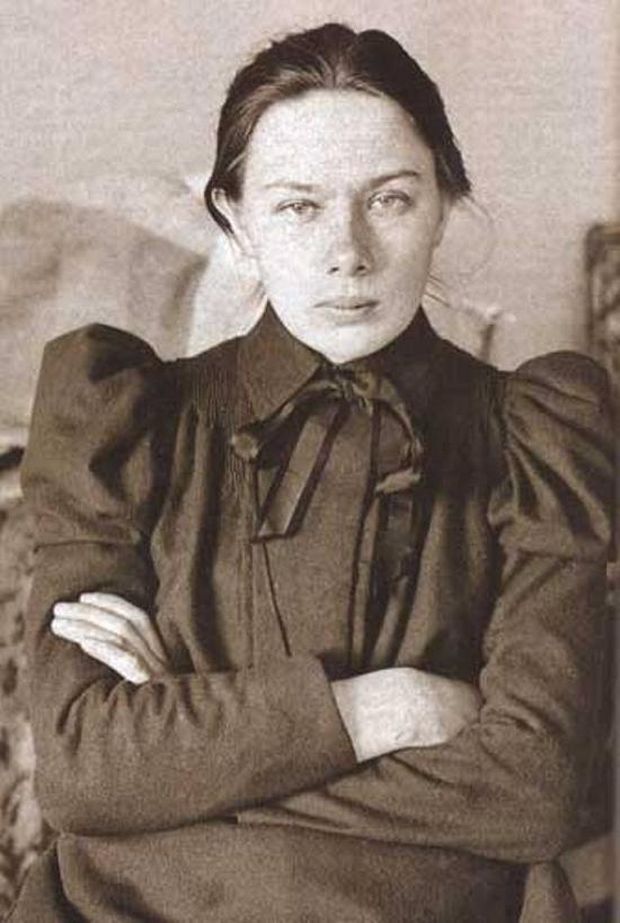

Nadezhda Krupskaya

She was the better half of Vladimir Lenin, but few know that Nadezhda was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and served as the Soviet Union’s Deputy Minister of Education. She was instrumental in the foundation of the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League and the Pioneer movement as well as the Soviet educational system, including the censorship and political indoctrination within it.

Nwanyeruwa

Nwanyeruwa, an Igbo woman in Nigeria, posed the very first major challenge to British authority in West Africa during the colonial period. On November 18, 1929, a census man named Mark Emereuwa had told her to “count her goats, sheep and people” prompting her to initiate a women’s war to protest the taxation of women and the unrestricted power of the Warrant Chiefs. The British dropped their tax plans; the women forced the resignation of many errant Warrant Chiefs.

Petra Herrera

During the Mexican Revolution that started in 1910, Petra rose above the ideals of the norm set for female soldiers (known as soldaderas). Petra, who initially disguised herself as a male, joined the ranks of Villa’s army and kept her identity a secret. She was denied credit for the siege of Torreon; as a result she formed her own troop of all-female soldiers and became a role model for the country’s women.

Asmaa Mahfouz

Asmaa is an Egyptian activist and one of the founders of the April 6 Youth Movement credited with helping to spark a mass uprising through her video blog posted one week before the start of the 2011 Egyptian revolution. She is a prominent member of Egypt’s Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution and one of the leaders of the Egyptian revolution.

Kathleen Neal Cleaver

Kathleen Neal Cleaver was a member of the Black Panther Party and the first female member of the Party’s decision-making body. She and other women, such as Angela Davis, made up around two thirds of the Party at one point, despite the notion that the BPP was overwhelmingly masculine. In 1968, she ran for California’s 18th state assembly district as a candidate of the Peace and Freedom Party.

We failed to mention Lolita Lebron!

Nice, but should also be in this list: André ‘Dédé’ De Jongh.

WWII… “In August 1941, she made a trial run. climbing a smugglers’ route over the Pyrenees and into Spain with two Belgians and a Scottish soldier in tow. Arriving at the British consulate in Bilbao, she was greeted with skepticism.

You’ve done what?!!!”

Countess Andrée de Jongh (November 30, 1916, Schaerbeek — October 13, 2007) was a member of the Belgian Resistance during World War II. She organized the Comet Line (Le Réseau Comète) for escaped Allied soldiers. After the war, she worked in leper hospitals in Africa.

Early life

Andrée Eugénie Adrienne de Jongh (nicknamed «Dédée») was born in Schaerbeek in Belgium, then under German occupation during the First World War. She was the younger daughter of Frédéric de Jongh, a headmaster and Alice Decarpentrie. Edith Cavell, a British nurse shot in the Tir National in Schaerbeek in 1915 for assisting troops to escape from occupied Belgium to the neutral Netherlands, was a heroine in her youth. She trained as a nurse, and became a commercial artist in Malmédy.

[edit] Second World War

After German troops invaded Belgium in May 1940, de Jongh moved to Brussels, where she became a Red Cross volunteer, ministering to captured Allied troops. In Brussels at that time, hiding in safe houses, were many British soldiers, those left behind at Dunkirk and escapers from those captured at St. Valery-en-Caux. Visiting the sick and wounded soldiers enabled her to make links with this network of safe-house keepers who were trying to work out ways to get the soldiers back to Britain.

In the summer of 1941, with the help of her father, she set up an escape network for captured Allied soldiers, which became later known as the Comet Line. Working with Arnold Deppé and Elvire De Greef-Berlemont («Tante Go») in the south of France, they established links with the safe houses in Brussels, then a route was found, using trains, through occupied and Vichy France to the border with Spain. The first escape attempt was unsuccessful, and all of the escapees were captured by the Spanish, with only two out of eleven reaching England, so de Jongh decided to lead the second attempt, a group of three men, personally.

In August 1941, she appeared in the British consulate in Bilbao with a British soldier, James Cromar from Aberdeen, and two Belgian volunteers, Merchiers and Sterckmans, having travelled by train through Paris to Bayonne, and then on foot over the Pyrenees. She requested support for her escape network, which was granted by MI9. She helped around 400 Allied soldiers to escape from Belgium, through occupied France to the British consulate in Madrid and on to Gibraltar. Andrée accompanied 118 of them herself. Airey Neave described her as «one of our greatest agents».

The Gestapo, using a traitor, captured her father, Frédéric de Jongh, in Paris in June 1943 and later executed him. De Jongh herself was betrayed and captured at a farmhouse in Urrugne, in the French Basque country, in January 1943 – the last stop on the escape line before the passage over the Pyrenees – during her 33rd journey to Spain. She was interrogated by the Gestapo and tortured, and admitted that she was the organiser of the escape network. Unwilling to believe her, the Gestapo let her live. She was sent first to Fresnes prison in Paris and eventually to Ravensbrück concentration camp and Mauthausen. She was released by the advancing Allied troops in April 1945. Many other members of the Comet Line were also captured. 23 were executed and hundreds of helpers were sent to concentration camps, where an unknown number died. Meanwhile, the line continued in their absence: in all, it returned around 800 Allied soldiers and airmen, continuing until Belgium was liberated in 1944.

For her wartime efforts, she was awarded the United States Medal of Freedom, the British George Medal, and became a Chevalier of the French Légion d’honneur. She also became a Chevalier of the Order of Leopold (Belgium), received the Belgian Croix de Guerre/Oorlogskruis with palm, and was granted the honorary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the Belgian Army. In 1985, she was made a countess.

[edit] Later life

After the war, she moved first to the pre-independence Belgian Congo, then to Cameroon, next to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, working in leper hospitals and finally to Senegal. In failing health, she eventually retired to Brussels.

[edit] Death

The Countess De Jongh died on Saturday, 13 October 2007, aged 90, at the University Clinic Woluwe-Saint-Lambert/Sint-Lambrechts-Woluwe, Brussels.[1][2] Her funeral service was held at the Abbaye de la Cambre/Abdij Ter Kameren, Ixelles/Elsene Brussels, six days later. She was interred in the crypt of her parents at the Schaarbeek Cemetery at Evere the same day.

[edit] References

^ «Andree de Jongh. Belgian resistance worker who braved extreme danger to smuggle Allied airmen out of Nazi-occupied territories.». London: The Guardian. 15 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

^ Martin, Douglas (18 October 2007). «Andrée de Jongh, 90, Legend of Belgian Resistance, Dies». New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-04. «Andrée de Jongh, whose youth and even younger appearance belied her courage and ingenuity when she became a World War II legend ushering many downed Allied airmen on a treacherous, 1,000-mile path from occupied Belgium to safety, died Saturday in Brussels. She was 90.»

[edit] Further reading

Eisner, Peter, «The Freedom Line» (1st edition), 2004. ISBN 0-06-009663-2

(French) Gubin, E., «DE JONGH, Andrée dite Dédée (1916–2007)» in E. Gubin, C. Jacques, V. Piette & J. Puissant (eds), Dictionnaire des femmes belges: XIXe et XXe siècles. Bruxelles: Éditions Racine, 2006. ISBN 2-87386-434-6

Obituary, The Times, 15 October 2007

Obituary, The Daily Telegraph, 18 October 2007

Obituary, The Guardian, 22 October 2007

The Comet line (Le Réseau Comète) was a World War II resistance group in Belgium/France which helped Allied soldiers and airmen return to Britain. The line started in Brussels, where the men were fed, clothed and given false identity papers before being hidden in attics and cellars of houses. A network of people guided them south through occupied France into neutral Spain and home via British-controlled Gibraltar.

Contents

[hide]

1 Routes

2 Creation and exploits

3 Notable members of the Line

4 Further reading

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

[edit] Routes

A typical route was from Brussels or Lille to Paris and then via Tours, Bordeaux, Bayonne, over the Pyrenees to San Sebastián in Spain. From there evaders travelled to Bilbao, Madrid and Gibraltar. There were three other main routes. The Pat line (after founder Pat O’Leary) ran from Paris to Toulouse via Limoges and then over the Pyrenees via Esterri d’Aneu to Barcelona. Another Pat line ran from Paris to Dijon, Lyons, Avignon to Marseille, then Nîmes, Perpignan and Barcelona. From Barcelona evaders were transported to Gibraltar. Another route from Paris (the Shelburne line) ran to Rennes and then St Brieuc in Brittany, where men were shipped to Dartmouth.

[edit] Creation and exploits

The Comet line was created by a young Belgian woman who joined the Belgian Resistance. Andrée de Jongh (nickname «Dédée») was 20 in 1940 and lived in Brussels. She was the younger daughter of Frédéric de Jongh, a headmaster, and Alice Decarpentrie. Edith Cavell, a British nurse shot in the Tir National in Schaerbeek in 1915 for assisting troops to escape from occupied Belgium to the neutral Netherlands, had been a heroine of Dédée’s in her youth.

In August 1941, Andrée de Jongh appeared in the British consulate in Bilbao with a British soldier, James Cromar from Aberdeen, and two Belgian volunteers, Merchiers and Sterckmans, having travelled by train through Paris to Bayonne and then on foot over the Pyrenees. She requested support for her escape network (later named Comet line) from the British military intelligence, granted by MI9, (British Military Intelligence Section 9), under the control of an ex-infantry major, Norman Crockatt and lieutenant James Langley, who had been re-patrioated after losing his left arm in the rear guard defence of Dunkerque in 1940.

With MI9 she helped 400 Allied soldiers escape from Belgium through occupied France to the British consulate in Madrid and on to Gibraltar. Neave described her as «one of our greatest agents.»[1] Later Neave organised gunboats from Dartmouth, Devon, to cross the Channel and run agents and supplies to the French resistance in Brittany and to return escaped POWs and evaders to Britain.

Comet Line members and the families took great risks, De Jongh escorting 118 airmen over the Pyrenees herself.

After November 1942 escape lines became more dangerous when southern France was occupied by the Germans and the whole of France was under Nazi rule. Many members of the Comet line were betrayed, hundreds were arrested by the Geheime Feldpolizei and the Abwehr and after weeks of interrogation and torture at places such as Fresnes Prison in Paris were executed or labelled Nacht und Nebel (NN) prisoners. NN prisoners were deported to German prisons and many later to concentration camps such as Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, Buchenwald concentration camp, Flossenbürg concentration camp,[2]

Prisoners sent to these camps included Andrée de Jongh, Elsie Maréchal (Belgian Resistance), Nadine Dumon (Belgian Resistance), Mary Lindell (Comtesse de Milleville) and Virginia d’Albert-Lake (American).

The authors of the official history of MI9 cite 2,373 British and Commonwealth servicemen and 2,700 Americans taken to Britain during World War II. The RAF Escaping Society estimated there were 14,000 helpers officially in 1945.[3] The Comet line inspired the 1970s BBC television series, Secret Army (1977–79).

[edit] Notable members of the Line

Andrée de Jongh, (aka Dédée) Line creator and chief. Arrested 15 January 1943. Survived several Nazi concentration camps. Awarded the George Medal

Frédéric de Jongh, (aka Paul). Dédée’s father. Arrested 7 June 1943. Executed 28 March 1944.

Baron Jean Greindl, (aka Nemo). Head of line in Brussels. Arrested 6 February 1943. Killed 7 September 1943.

Elvire de Greef, (aka Tante Go). Organiser in South France. Escaped arrest and survived. Awarded the George Medal

Jean-François Nothomb, (aka Franco). Succeeded Dedee in France. Arrested 18 January 1944. Survived several Nazi concentration camps. Awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Comte Jacques Legrelle (aka Jerome), organised and operated line in the Paris area, linked theBelgium part of line to South of France. Was captured, tortured, sent to concentration camps and survived. Awarded the George Medal.

Comte Antoine d’Ursel (aka Jacques Cartier). Succeeded Nemo in Brussels. Died crossing Franco-Spanish border 24 December 1943.

Micheline Dumon (aka Michou), Operated line in 1944. Escaped arrest and awarded the George Medal.

[edit] Further reading

The story of the Comet Line is fully told in the book The Little Cyclone written by Airey Neave who whilst working for MI9 was responsible for overseeing this line and to aid it wherever possible.

Other accounts appear in the books Saturday at MI9 also by Airey Neave, Home Run by John Nichol & Tony Rennel, and MI9 – Escape & Evasion by James Langley & M. R. D. Foot.

Return Journey by Major ASB Arkwright includes a first hand account of three British Officers who were brought to freedom by the line after escaping from a POW camp.

«Riding the Comet» is a stage drama by Mark Violi. The play focuses on a rural French family helping two American GIs return safely to London days after the D-Day invasion. This play premieres at Actors’ NET of Bucks County (PA) in September 2011.[4]

[edit] See also

Andrée de Jongh

French Resistance

Belgian Resistance

Shelburne Escape and Evasion Line (Operation Bonaparte)

Phil Lamason

Roy Allen

Jacques Desoubrie

KLB Club

[edit] References

^ Home Run – Escape from Nazi Europe 2007. John Nichol and Tony Rennell. (Penguin Books)]

^ (English) Marc Terrance (1999). Concentration Camps: Guide to World War II Sites. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1-58112-839-8.

^ Home Run – Escape from Nazi Europe – 2007 p470 – John Nichol and Tony Rennell – (Penguin books)

^ Violi, Mark. «Riding the Comet».

Does Phoolan Devi qualify a mention? I think she stood tall for several reasons

And what about Joan of Arc

Angela Davis was never a member of the Black Panthers.She was a member of the Communist Party but left it in 1991 to help found the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism…whatever that might be

This title is a lie, since the fiercest revolutionary – man or woman – in history is Emma Goldman.

Yes, my man, JOA !!! cocorico ! it s her who underlined first the needs for pytchiatric hospital ! ” i heard god ! told me to free france from those roosbiffs by myself !!!” remember JOA , u whole bunch of brits….

María Josefa Gabriela Cariño Silang (19 March 1731 – 20 September 1763) was a Filipino revolutionary leader and the wife of the Ilocano insurgent leader, Diego Silang. Following Diego’s assassination in 1763, she led the insurgency for four months before she was captured and executed by the colonial government of the Spanish East Indies.

After being widowed by her first husband, Gabriela met insurgent leader Diego Silang and married him in 1757. In 1762, as part of what would later be known as the Seven Years’ War, Britain declared war on Spain, which caused the British occupation of the Philippines. After British naval forces captured Manila in October 1762, an emboldened Diego sought to initiate an armed struggle to overthrow the Spanish functionaries in Ilocos and replace them with native-born officials. He collaborated with the British occupiers, who appointed him governor of the Ilocos region on their behalf and promised military reinforcement to help in the fight against the Spanish. This reinforcement was, however, never delivered. During this revolt, Gabriela became one of Diego’s closest advisors and his unofficial aide-de-camp during skirmishes with Spanish troops. She was also a major figure in her husband’s collaboration with the British occupiers. Spanish authorities retaliated by offering a reward for Diego’s assassination. Consequently, his two former allies Miguel Vicos and Pedro Becbec killed him in Vigan on May 28, 1763.

The Order of Gabriela Silang is the sole third class national decoration awarded by the Philippines, and whose membership is restricted to women.

In memory of Silang, the provincial hospital of Ilocos Sur was named the Gabriela Silang General Hospital.

The organisation and party list GABRIELA (“General Assembly Binding Women for Reforms, Integrity, Equality, Leadership, and Action”), which advocate’s women’s rights and issues, was founded in April 1984 in her honour.

A statue of Silang on horseback was installed by the Zóbel de Ayala Family at the corner of Ayala and Makati avenues in Makati City, the nation’s financial centre. The metal monument was cast by José M. Mendoza in 1971, and was inaugurated by Silang’s descendants Gloria Cariño and Mario Cariño Merritt.

Another monument stands in the town plaza of Pidigan, Abra, as a reminder of the heroine, whom the town claims as a native.

The Tangadan Welcome Tunnel in Abra now has the Gabriela Silang Memorial Park with a monument to the heroine

Gabriela Silang, not mentioned…..

Can we give an honorable mention to Ronda Rousey? I can’t confirm, nor deny that Anonymous has the hots for her. Okay, I can confirm that it does…

Very informative article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.