In 1984, James Stewart, a graduate student, discovered an unusually high number of miscarriages at the Digital Equipment Corp while working through school as a health and safety officer. Digital Equipment agreed to fund a study, helmed by professor Harris Pastides to investigate the matter. In 1986 it was found that women working at the plant experienced twice the number of miscarriages compared to the average rate.

Tech companies including International Business Machines Corp., Intel Corp., and about a dozen other top technology companies grouped under the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) sent experts who gathered and met with Pastides, scrutinizing his findings and criticising his work at a hotel near Bradley International Airport.

“That was a day I remember being at a tribunal,” Pastides said, and the atmosphere “bordered on hostility. I remember being shellshocked.”

They did, however, agree to fund three more studies into the matter. Then something miraculous happened: unlike most industry-funded research, instead of aligning closely with what the industry expected, all three studies showed a doubling of miscarriage rates for women working in their plants.

The companies blamed a group of toxic chemicals commonly used in chip assembly and claimed that they would phase them out completely by 1995. (Interestingly a recent SIA-commissioned study found that “Work in the US semiconductor industry, including semiconductor wafer fabrication in cleanrooms, was not associated with increased cancer mortality overall or mortality from any specific form of cancer” but apparently SIA’s website made no mention of miscarriage rates)

Unfortunately, this part of the arrangement turned out exactly as you would expect when chipmaking got outsourced to Asia — partly due to the lack of control over foreign manufacturers who independently behave as they will and partly due to the concept of “Fabless Chip Manufacturing”, wherein American companies like AMD or Nvidia design chips and export the actual manufacturing process to companies in countries with cheaper labor, fewer… restrictions… and in some cases ignorance of the dangers of these chemicals.

Bloomberg Businessweek obtained data from the companies that women continued to be exposed to these chemicals, at least until 2015. To this day many may still be exposed. And the ramifications of this show in the very same rates of miscarriage.

Further, there may be other chemicals to blame, chemicals which have not even been disclosed which cause other devastating health problems. Cancer, for example.

A South Korean physician named Kim Myoung-hee would stumble upon another curious case:

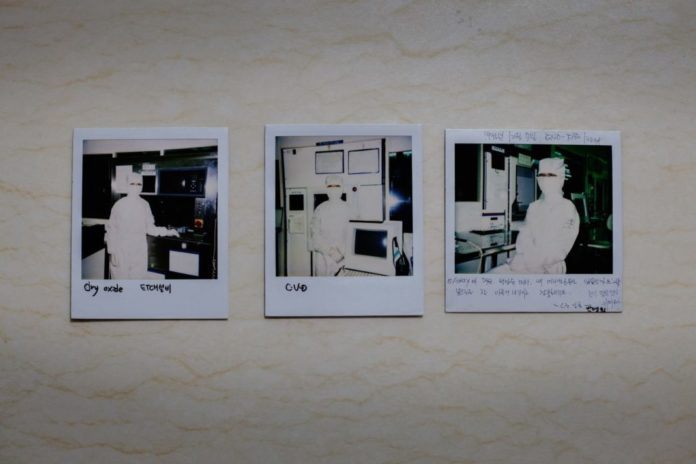

Two young South Korean women, who worked side-by-side at the same Samsung Electronics workstation and were exposed to the exact same chemicals, developed the same aggressive form of leukemia (one which typically affects only 3 out of every 100,000 South Koreans). They died within 8 months of each other.

Soon other cases were revealed at Samsung and other microelectronics companies. Kim started digging deeper: “I had no idea that this is a chemical industry, not the electronics industry.”

(Speaking of chemicals, Gordon Moore is a chemist and a founder of Intel. He worked with physicist Jay Last to found the process used to print circuits onto chips. He had this to say in an interview for an oral history project for the Chemical Heritage Foundation:

“We were putting into industrial production a lot of really nasty chemicals,” Last said. “There was just no knowledge of these things, and we were pouring stuff down into the city sewer system.”

Moore noted that when workers dug up the pipes beneath Intel, the “bottom was completely eaten out the whole way along, and that was just about the time we really started recognizing how much you had to take care of this.”)

Kim would find that every study published since the 1990s claimed that the global semiconductor industry had stopped the usage of miscarriage-causing chemicals by 1995. Strangely, she found that this did not seem to affect the young South Korean women workers her associates interviewed — some would go months to a year without menstruating.

In 2013, Kim finally managed to obtain national health-insurance data, circumventing the lack of cooperation she faced from South Korean chipmakers. The results of her study showed a familiar trend: women in their 30s had a miscarriage rate nearly as high as their American counterparts decades prior.

“This was not the result I had expected,” Kim said.

According to Kim, it is impossible to estimate the number of women exposed to the toxic chemicals. Turnover rates at semiconductor plants are high, and estimates of 120,000 female employees are probably on the low side.

It is easy to forget that in these statistics lie thousands of individuals.

Take Han Hye-kyung, a former worker at a Samsung LCD factory:

“I just hate Samsung. More and more. I hate Samsung”

Her mother continued on her behalf because she had difficulty speaking:

“Hye-kyung started work in 1995 and quit the job in 2001. In September 2005 she was diagnosed with a brain tumor. She quit Samsung because her period completely disappeared… But even after she quit, her period was still irregular. She got the brain tumor while she was being treated for her irregular periods, you know?”

Samsung, in particular, would wage war against former employees, hiring South Korea’s top lawyers to combat their workers’ claims for compensation. According to Bloomberg, the company’s execs have been secretly recorded offering payouts to families who were willing to withdraw their claims. Hush money.

By 2014, Samsung finally apologized for how it treated the families of victims, and privately arranged to compensate workers past and present for illnesses and deaths. Payouts are inconsistent though, and it still denies any causal link between illnesses and its processes.

When Bloomber interviewed Pastides, he said: “The fact that women around the world were still being subjected to things that experts, including corporate leaders, decided should not be used in the workplace — to me that is an extremely sad story, and a loss for public health.”

Sources: Bloomberg, NCBI, The Independent, LevyLaw, Semiconductors.org

It’s not just woman, it’s a higher cancer rate amongst all people that work in the Silicon industry. I am one of the lucky ones that survived, but I know many who did not. It’s much bigger than any one will admit.

i can discover numerous good answers if i have difficulty!

best albion online gold supplier http://www.3diablogold.com/potions-as-well-as-consumables-are-quite-significant-in-albion-online/