A village lady lights a candle to the saint and beseeches that her juvenile son gets well, and the potato crop should be a big one this year. The prayers of her and the people who visit him have been answered as they claim. He listens to their prayers even lying dead in his grave, the name of their saint – Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

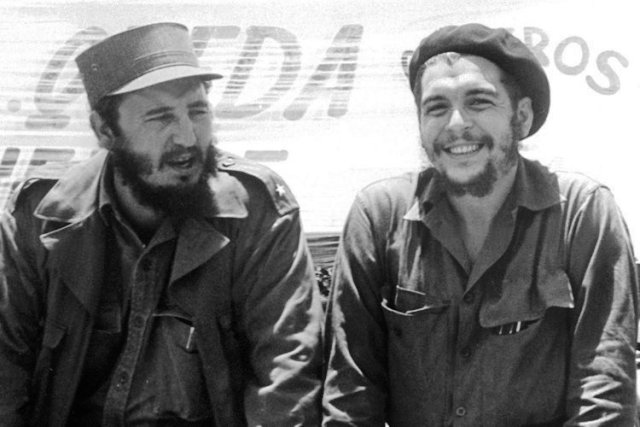

In the summers of 1928 a child was born to an aristocratic left winged family that originated from Spanish and Irish roots. Although he had asthma, he was an excellent sportsman, a keen rugby player as well as a skilled player of the chess game. During his medical studies at the University of Buenos Aires, Guevara was persuaded by a good friend to consider a motorbike getaway across South America. And this trip changed him for a revolution because he said he saw a lot of poverty and injustice. After meeting Fidel Castor in 1955 in Mexico City, he immediately decided to participate in his agenda and overthrow the Cuban autocrat Fulgencio Batista. He decided to join as a medical officer in Castor’s regime but due to the heavy loss he went on fighting in the front line which made him prominent in the eyes of Castro as well as other in the army.

According to a few reports, around five hundred people were killed on the orders of Guevara in that duration. Unfortunately, that is the reality that adorns with those posters, graffiti and T-shirts of Guevara itself, wherein Guevara’s refusal for taking payment regarding his government duty is still talked about with admiration. One other suggestion is that Castro and Guevara fell entirely around the policy. What is well known is the fact that Guevara penned a letter to Castro saying that different nations around the globe wanted his “modest” efforts and went on saying that he would leave Cuba to bring “justice” to other nations and take on new battlefields. His first out of the country trip took him to Congo in which Guevara hoped to mobilize Marxist guerrillas from Simba and conquer its government. The expedition was obviously a complete failure as a result of the constant fighting within its people. Deflated, Guevara went back to South America, but this time he was going to lead a revolt in Bolivia.Though Guevara’s group of 50 guerrillas scored some initial successes, his fortunes started to flip as soon as the United States government got involved. Once they learned Guevara was in Bolivia, the United States dispatched its special forces and CIA spy to train and equip the Bolivian military with weapons.

Che does not appear to be like a saint. But there is a factor to consider. The biggest of sinners do become saints. Several models of this can be seen everywhere in past; one can take into the account of St. Paul. Of course, Che was killed before he had a chance to see what he had done, how many people he had killed but with what he had done throughout the years he might not have done that, but yet again who knows. So take an example from his life, his failures, his decisions, his career, the path he chose to follow, his self-destruction and immolation of the society and that he died for our sins. If this is the cost he paid for us, then let the sacrifice be an NO for the minds coming under this cerebrally created hell, perhaps he deserves the title given to him by the people who visit his grave and call him a saint. Maybe then, we must burn a candle to him and pray, that we do not want any more guerrillas.

Truth about Ernesto "#Che" Guevarahttps://t.co/iUWTmG7d9Y

— Anon.Dos (@anondos_) October 29, 2015

You want to support Anonymous Independent & Investigative News? Please, follow us on Twitter: Follow @AnonymousNewsHQ

This Article (The Darkside of Che Guevara) is free and open source. You have permission to republish this article under a Creative Commons license with attribution to the author and AnonHQ.com.

The video is quite imprecise, sarcastic and until defamatory.

This guy (the creator of the video) cites no reliable sources where someone could corroborate his story. It is also significantly biased and it looks a lot like the common articles/videos of the mercenaries of the neoliberals/fascists who are disguised of “researchers” or journalists (in this era of disinformation) .

With so many twisted pictures, it’s enough to me know that the courage and the manhood of an instant in the life of a man like “Che” is worth more than the entire life of a “trained liar”, submissive slave of the oligarchs, which hides in a cowardly manner behind a screen and a keyboard.

I read the data that you publishes, even I share some of your articles although this time I’m -really- very surprised with this video (that you have embedded on your website, facebook, even in Twitter).

Have you verified the reliability of this “source” this time? Really?

I am Argentine, and I have read “a lot” about “Che”.

I sympathize with the left-parties although, over all, I am an anarchist, so you will understand that any political movement -and their leaders- for me are irrelevant.

But the truth is the truth.

His sources are listed in the description of the video an they include Gueverra’s own biography. Do you have any reason to doubt any of the information in this video because your comment seems baseless and without merit.

Here’s the truth about Che from someone who lived it. It’s disgusting how Che is romanticized. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzaAS_gi_QM

have you checked his Bibliography??? his bibliography are opinions and other articles without bibliography. I can´t say he was an exceptional person and yes he killes people, but what this guy is saing is bullshit, do your own reasearch do not trust this guy

Poorly written article.

“He decided to join as a medical officer in Castor’s regime but due to the heavy loss he went on fighting in the front line which made him prominent in the eyes of Castro as well as other in the army”

What is that supposed to mean?

truly vacuous. How an analysis can manage to assess Cuba without reference to the blockade by the USA. Without reference to the terrorism directly and indirectly by the USA and by the need to defend Cuba and keep it on a constant war footing because of the aggression of …the USA. Anonymous really needs to have some sort of off switch for people who cannot even be bothered to read the histories of those it attempts to defame.

Behind Che Guevara’s mask, the cold executioner

Matthew Campbell. Times Online, September 16, 2007.

A ROMANTIC hero to legions of fans the world over, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the poster boy of Marxist revolution, has come under assault as a cold-hearted monster four decades after his death in the Bolivian jungle.

A revisionist biography has highlighted Guevara’s involvement in countless executions of “traitors” and counter-revolutionary “worms”, offering a fresh glimpse of the dark side of the celebrated guerrilla fighter who helped Fidel Castro to seize power in Cuba.

“Attacking an almost legendary figure is not an easy task,” said Jacobo Machover, author of The Hidden Face of Che. “He has so many defenders. They have forged the cult of an untouchable hero.”

The Argentine-born Guevara has become ever more fashionable, his prerevolutionary adventures as a medical student dramatised to great acclaim in the film The Motorcycle Diaries and his bearded visage an icon of chic on T-shirts and even bikinis.

Machover, a Cuban exiled in France since 1963, blames the hero worship on French intellectuals who flocked to Havana in the 1960s and fell under the charm of the only “comandante” who could speak their language.

They turned a blind eye to anything that did not fit in with their idealised image of Guevara. A prolific diarist, Guevara nevertheless wrote vividly of his role as an executioner. In one passage he described the execution of Eutimio Guerra, a peasant and army guide.

“I fired a .32calibre bullet into the right hemisphere of his brain which came out through his left temple,” was Guevara’s clinical description of the killing. “He moaned for a few moments, then died.”

This was the first of many “traitors” to be subjected to what Guevara called “acts of justice”.

There was seldom any trial. “I carried out a very summary inquiry and then the peasant Aristidio was executed,” he wrote about another killing. “It is not possible to tolerate even the suspicion of treason.”

Guevara found particularly “interesting” the case of one of his victims, a man who, just before being executed, penned a letter to his mother in which he acknowledged “the justice of the punishment that was being dealt out to him” and asked her “to be faithful to the revolution”.

Such reflections sent a chill down the spine of the author. “The guilty, or those presumed to be so, were expected to recognise the benefits of their death sentence,” he said.

Guevara also carried out mock executions on prisoners. Relieved to discover that he had not been shot, one of the victims, wrote Guevara in his diary, “gave [me] a big, sonorous kiss, as if he had found himself in front of his father”.

The cigar-chomping Guevara went on to become head of the Cuban central bank where he famously signed banknotes with his nickname Che. But his first job after the rebels marched in triumph into Havana in 1959 was running a “purifying commission” and supervising executions at Havana’s La Cabana prison.

“He would climb on top of a wall . . . and lie on his back smoking a Havana cigar while watching the executions,” the author quotes Dariel Alarcon Ramirez, one of Guevara’s former comrades in arms, as saying.

It was intended as a gesture of moral support for the men in the firing squad, says Machover. “For these men who had never seen Che before, it was something really important. It gave them courage.”

In a six-month period, Guevara implemented Castro’s orders with zeal, putting 180 prisoners in front of the firing squad after summary trials, according to Machover. Jose Vilasuso, an exiled lawyer, recalled Guevara instructing his “court” in the prison: “Don’t drag out the process. This is a revolution. Don’t use bourgeois legal methods, the proof is secondary. We must act through conviction. We’re dealing with a bunch of criminals and assassins.”

Machover blames French intellectuals such as Régis Debray, who became an acolyte of Guevara and professor of philosophy at Havana’s university in the 1960s, for the canonisation of this far from saintly figure.

“The legend forged around Che is first and foremost a French creation that became international with time,” says Machover. Jean-Paul Sartre, the existentialist author who visited Havana with Simone de Beauvoir in 1960, also played a role, describing Guevara as “the most complete man of his epoch”.

Today the cult of Che is thriving. He was recently voted “Argentina’s greatest historical and political figure” and ceremonies will be held all over the Andes and the Caribbean to mark the 40th anniversary of his death on October 9. He was executed in Bolivia where he was fomenting rebellion against the government.

Gustavo Villoldo, a former CIA operative who said he helped to bury Guevara, plans to auction a scrapbook in which he kept a strand of his hair, photographs of the body and a map of the hunt for the guerrilla leader.

“I’m doing it for history’s sake,” he said. Not only that, perhaps: he expects to fetch up to £4m. Viva la revolucion.