In 2001, about 1% of Portugal’s entire population was addicted to heroin or any related narcotic drugs considered illegal. Portugal was ranked number one in the European Union for the use of narcotic-related drugs in 1999, an already difficult period for the country.

According to historians, the drug problem in Portugal had its genesis from the Carnation Revolution – a bloodless military coup which overthrew the 50-year dictatorship of the Estado Novo regime in 1974.

Before the revolution, Portugal was said to be one of the drug-free countries in Western Europe. But the Carnation Revolution, which many sociologists consider as the agent of change in Portugal’s history, also came with a price that required strategic thinking before it could be paid. The revolution sparked a chaotic transition from autocracy to democracy. The Portuguese society struggled to define itself as a new nation that could open up the country to the rest of the world.

The new regime pushed through a rapid and hasty programme of decolonization of its territories. The next few years that followed the revolution saw Portugal giving up its colonies Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Cape Verde Islands, Sao Tome and Principe and Angola. As these countries became independent, soldiers and civilians who were stationed in these newly-freed colonies returned to the country with a variety of drugs.

The country also opened up its airspace, water and land borders, making travel and exchange much easier. Due to this new found freedom, Portugal became a natural gateway for trafficking hard drugs across the European continent. Drug use became part of the culture of liberation, and the use of hard narcotics became popular. Eventually, it got out of hand and drug use became difficult for the then government to fight.

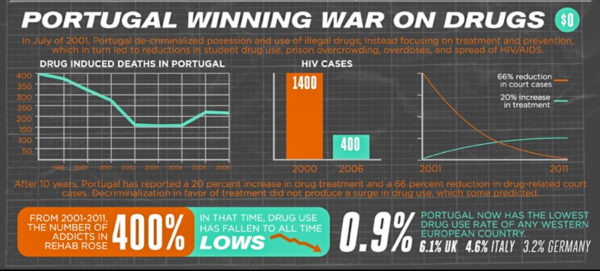

But when everybody thought the country had lost the drug addiction fight, in 2001, the Portuguese government did something that other governments in Europe and the United States would never have considered. It decriminalized all hard drug-related offences.

The new law the government promulgated was that if someone is found in the possession of any hard drug, ranging from marijuana to heroin, the person is sent to a three-person Commission called the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction (DDA). The DDA is made up of a lawyer, a doctor and a social worker. The commission recommends treatment or a minor fine. In most cases, the person is sent off without any penalty, but only if the commission thinks there is enough evidence to show that the person regretted their actions and won’t use these drugs again.

The DDA commission was fully resourced by the Portuguese government. This allowed clinics, special treatment centers, and mobile clinics to be opened across the country to target drug addicts. The main goal was to treat addicts as patients, rather than spending money and keeping them behind bars as criminals. The government started the treatment programme with $49 million in 2001. A year later, the amount was increased to $77 million. Even during the financial crises in 2008, the government was reluctant to cut down spending on the treatment programme.

Today, Portugal’s alternative methods to fight its drug problem are paying off. According to a study published by Transfer Drug Policy Foundation – a United Kingdom think-tank that advocates drug decriminalization – drug overdose, which killed many people in the past in Portugal, has dropped significantly.

The Open Foundation Society has also revealed in a report that Portugal’s drug treatment programme has prevented first-time drug use and delaying the age of drug use. According to the report, drug use among 15 to 19-year-olds, a group most often the target of anti-drug campaigns, has decreased.

In general, the number of people indicating to have been using drugs as of November 2016 has declined compared with 2001 figures, with an average opioid addiction of 0.5%. Although the country has not completely eliminated drug abuse in the country, the treatment programme has proved a huge success.

When Portugal decided to decriminalize drugs in 2001, the United Nations opposed it. But during a recent conference in Vienna, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) called the Portuguese approach an example of best practices, because it puts health and welfare in the centre and is based on the respect of human rights. INCB is the independent control body for the implementation of United Nations drug conventions.

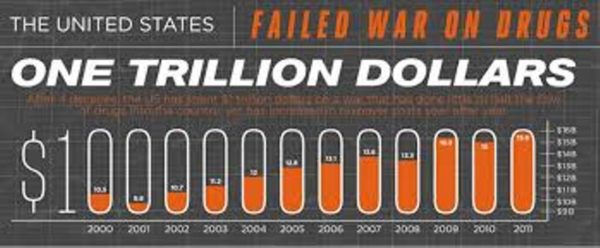

If the United Nations, who opposed the policy initially, is now making a U-turn, then it tells us how successful Portugal has been with the policy. There are many lessons that the United States can learn from this policy, considering the fact that the country is grappling with the same issue. The United States’ war on drugs has failed completely. It only puts people in jail, wasting human resources and money. To bring change, the US should heed some lessons from Portugal and swallow its pride.

This article (Portugal Treats Drug Addicts as Patients, not as Criminals, Records Massive Success in just 15 Years) is a free and open source. You have permission to republish this article under a Creative Commons license with attribution to the author and AnonHQ.com.

Supporting Anonymous’ Independent & Investigative News is important to us. Please, follow us on Twitter: Follow @AnonymousNewsHQ