Dr. Sonnet Ehlers of South Africa was on call one night four decades ago when a distraught rape victim walked in. Her eyes were lifeless; she resembled a living corpse.

“She looked at me and said, ‘If only I had teeth down there,'” Ehlers, a 20-year-old medical researcher at the time, recalled. “I promised her that one day I’d do something to help people like her.”

Rape-aXe was born forty years later.

Ehlers is distributing female condoms in the various South African cities hosting World Cup soccer games.

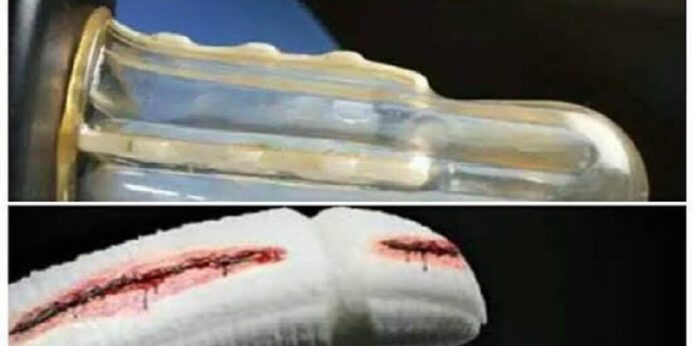

The latex condom is inserted like a tampon by the woman. According to Ehlers, its inside is lined with jagged rows of teeth-like hooks that attach to a man’s penis during penetration.

Only a doctor can remove it once it has become lodged, which Ehlers hopes will be done with authorities on standby to make an arrest.

“It hurts, and he can’t pee or walk with it on,” she explained. “If he tries to remove it, it will tighten even more… but it does not break the skin, and there is no danger of fluid exposure.”

Ehlers stated that she sold her home and car to fund the project, and that she intended to distribute 30,000 free devices under her supervision during the World Cup.

“I consulted engineers, gynecologists, and psychologists to help with the design and ensure its safety,” she explained.

Following the trial period, they will be available for around $2 per piece. She is hoping that the women will report back to her.

“The ideal situation would be for a woman to wear this on a blind date… or to an area she’s not comfortable with,” she explained.

The mother of two daughters stated that she visited prisons and spoke with convicted rapists to determine whether such a device would have caused them to reconsider their actions.

Some speculated that it would, according to Ehlers.

According to critics, the female condom is not a long-term solution and exposes women to additional violence from men trapped by the device.

It is also a form of “enslavement,” according to Victoria Kajja, a fellow for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Uganda, an east African country. “The victim’s fears, the act of wearing the condom in anticipation of being assaulted, all represent enslavement to which no woman should be subjected.”

According to Kajja, the device constantly reminds women of their vulnerability.

“It not only gives the victim a false sense of security, but it also causes psychological trauma,” she added. “It also does not help with the psychological issues that arise as a result of assaults.”

Its one advantage, she claims, is that it allows justice to be served.

Human Rights Watch and Care International, two South African rights organizations, declined to comment.

According to Human Rights Watch, South Africa has one of the highest rape rates in the world. According to Human Rights Watch, a 2009 report by the nation’s Medical Research Council found that 28 percent of men surveyed had raped a woman or girl, with one in every 20 saying they had raped in the previous year.

Rape convictions are uncommon in most African countries. Affected women do not have immediate access to medical care, and DNA tests to provide evidence are prohibitively expensive.

“Women and girls who are victims of these violations are denied justice, contributing to the normalization of rape and violence in South African society,” Human Rights Watch says.

Women in South Africa take drastic measures to avoid rape, according to Ehlers, with some wearing extra tight biker shorts and others inserting razor blades wrapped in sponges in their private parts.

Critics have accused her of inventing a medieval rape deterrent.

“My device is medieval, but it’s for a medieval deed that’s been around for decades,” she explained. “I believe something must be done… and this will cause some men to reconsider assaulting a woman.”