Recent effects of the El Nino that hit our oceans hit our oceans late 2015, has come to light.

It will soon be time to bid good riddance to the El Nino of 2015-2016. The effects of the natural occurrence has been well documented over the past months, showing devastating mass bleaching events of coral reefs worldwide.

The Great Barrier Reef is one ecosystem of particular great concern. With the additional stress of anthropogenic induced climate change and the effects of the El Nino, driving warm waters into the western Pacific Ocean, the bleaching event hitting the reef is likely to be the “biggest environmental disaster to hit Australia,” says Dr Justin Marshall, a professor at the University of Queensland who has studied the reef for three decades.

A series of surveys conducted on the Great Barrier Reef by Australia’s National Coral Bleaching Task Force, concluded that, “Between 60 and 100 percent of corals are severely bleached on 316 reefs, nearly all in the northern half of the Reef.” The survey monitored 911 reef sites and found bleaching on 93 percent of them. To put this destructive phenomenon into perspective, the area bleached is approximately the size of Scotland.

“Before this mass bleaching started, we already were at the point of losing 50% of the coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef. This, I think, will probably take another 50% off what was left,” Marshall says.

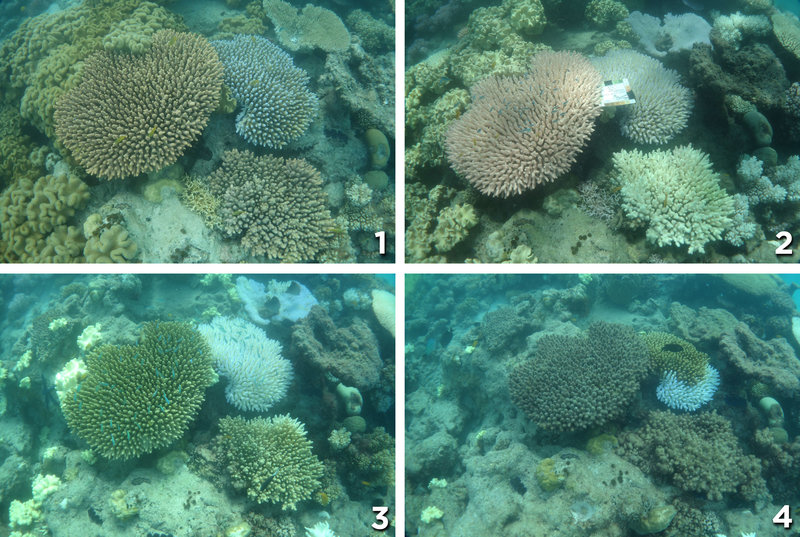

Over the past 6 months, Marshall, his colleagues and the citizen science project, Coral Watch, have monitored and documented the degradation of reefs located around Lizard Island, one of the worst hit area’s that was once described by Sir David Attenborough, as one of the most magical places on Earth.

Marshall and his team photographed the same coral formations multiple times over the 6 month period, demonstrating the pace of the combined El Nino and climate change effects.

Corals as we know, are highly sensitive species. Bleaching can be induced through a multitude of parameter fluctuations, whether that be a change in temperature and parameters, overexposure to sunlight, pollution, and low tides.

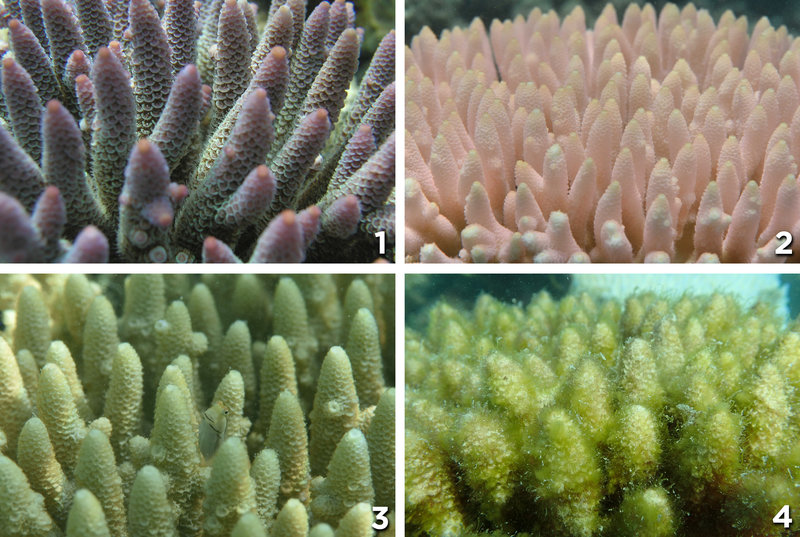

“Coral bleaching occurs when the living organisms that make up coral reefs expel the colourful, photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae, that normally live inside their bodies, and provide them with food. Those algae give coral reefs their colour and disappear when the reefs are exposed to stressful climatic conditions, such as temperatures even a few degrees higher than normal.” If water cools soon enough, the zooxanthellae can return, but prolonged bleaching will result in the death of the coral, and much more. The loss of coral cover makes reefs less hospitable for many marine organisms, thus leading to a loss of biodiversity.

The final image of the series showing the fate of corals subjected to bleaching.

Marshall believes that the mass bleaching event is linked to global climate change. “Mass coral bleaching’s have only been happening for 20 years, and they are irrevocably, totally, absolutely linked to man-induced climate change.”

It is no secret that concern is growing about reefs worldwide. “We are currently experiencing the longest global coral bleaching event ever observed,” C. Mark Eakin, the Coral Reef Watch coordinator at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Maryland, tells The New York Times. “We are going to lose a lot of the world’s reefs during this event.”

Now that Australia’s summer is coming to an end and the water is cooling down, there is a chance that some of the bleached coral may recover.

A mass coral bleaching event hit the Wakatobi Marine National Park in Indonesia 4 times during the 1998 El Nino. The resilience of this staggered scientists, showing the degrading reef recovering back to a similar original state after 3 months.

Unfortunately for the Great Barrier Reef, recovery is likely to happen over the course of years, potentially even decades. The factors in reef resilience do variate among a global scale; for example, corals at greater depths have a better chance at surviving increased surface temperatures. Area’s subjected to excessive sediment, pollution and the fishing of environmentally important species have lower resilience to bleaching events.

If coral reefs are to survive in the Anthopocene, co2 levels in the atmosphere will have to be reduced. Marshall adds “I will probably never see the Great Barrier Reef in the state that it was in six months ago ever again.”

You want to support Anonymous Independent & Investigative News? Please, follow us on Twitter: Follow @AnonymousNewsHQ

This article (New Images Show the Exponential Rate of Bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef) is a free and open source. You have permission to republish this article under a Creative Commons license with attribution to the author and AnonHQ.com.